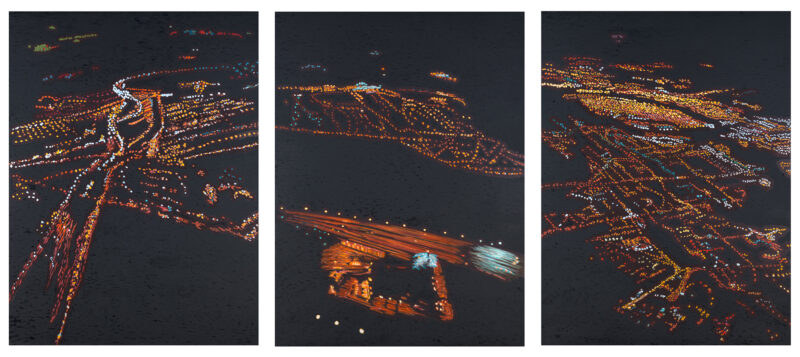

Metropolitan Area Triptych

Jacquette, Yvonne Helene

2007

Artwork Information

-

Title:

Metropolitan Area Triptych

-

Artist:

Jacquette, Yvonne Helene

-

Artist Bio:

American, born 1934

-

Date:

2007

-

Medium:

Oil on canvas

-

Dimensions:

54 x 121 1/2 in

-

Credit Line:

Wichita Art Museum, S.O. "Bud" Beren Memorial Funds contributed by the Murdock Society of the Friends of the Wichita Art Museum, Louise Beren and the Beren Memorial Fund

-

Object Number:

2008.5a,b,c

-

Display:

Not Currently on Display

About the Artwork

Yvonne Jacquette is a portrait painter of metropolitan America. The scope of her vision is vast, for her point of view (her actual vantage point) is from high above the street, and her subjects cross the globe, from Chicago to Minneapolis, San Francisco, Hong Kong, and Tokyo. But it is unquestionably New York which she celebrates most—and for which she is most celebrated. Every facet of New York seems to attract her: the buildings, bridges, water tanks, waterways, signs, lights, and—neon. All seen at night. The fourth dimension in art is time, and in Ms. Jacquette’s painting two temporal concerns are constant: the immobile and the nocturnal. As in the paintings of Edward Hopper, there is the sense that all movement has been frozen; that the world stopped at the very moment she caught it. Unlike Hopper, she has no interest in the shadows cast by the sun; rather, it is the brilliance and mystery of artificial light against the dark sky that attracts her.

Our great cities are the modern world’s contribution to the history of monuments throughout civilization, and Yvonne Jacquette’s paintings uphold their monumentality. They do so through her nocturnal vision, which emphasizes contrast, and through scale. Not only are her canvases unusually large, but her compositions seem to encompass an immeasurable space and weight. Her elevation of the cityscape is a departure from the norm. Until about 1900, painters most often chose to depict America as open landscape. Then, led by Robert Henri and others of the so-called “Ashcan” school, the urban landscape—especially when featuring its gritty reality—came to be seen as a way to embrace modern life and to promote progressive social change. Henri and Sloan painted rooftop water tanks from a low vantage point to emphasize the way they dominate those living under them. Jacquette rises above the everyday, thereby encouraging us to contemplate more abstract, or perhaps more cosmic, questions about our relationship to the city. With no one else visible in her vast urban landscapes, are we to think that it is all ours? Or is there any room for us at all?